Happy Valentine’s Day, Human Readers!

Now that we’ve gotten that out of the way, let’s get back to talking about the US-China trade talks.

The negotiations continue this week as representatives from both sides meet in Beijing. Expectations are high that they will eventually iron out a deal, possibly after extending the March 2 deadline.

However, as the Policy Change Index (PCI) cautions against, it would be wishful thinking to suppose China will make major concessions on the thorny, lingering issues — if a deal is ever reached. And the reason for that is fundamental to the Chinese system.

Policymaking in Beijing operates in a Soviet-style model that places propaganda — or, in Vladimir Lenin’s words, the “economic education” of the people — before policy implementation. China has followed this paradigm not only at the beginning of Deng Xiaoping’s reform program but also through the reform speedup under Jiang Zemin and its slowdown under Hu Jintao and, now, Xi Jinping. In these episodes, PCI-China picks up changes in propaganda months before the policy shifts.

The US demand from China — such as abandoning industrial policy and protecting intellectual property rights — falls into the Soviet model because it’s a structural change in policy. It can happen, but that PCI-China hasn’t picked up any signs means it’s not happening just yet.

It’s unclear how resolute President Trump was when he said a deal “must include real, structural change” in his State of the Union address. But if it was a must-have, there may be no deal.

COMMUNITY NEWS

The Policy Simulation Library, an open-source platform for public policy discussion, held its second meetup at AEI in late January.

Kevin Perese of the Congressional Budget Office gave an update on the exciting Transparency Initiatives at the agency, which releases data, source code, and interactive tools behind the models it develops. Richard Evans of the University of Chicago presented an overlapping generations model of the US economy and demonstrated how to use it for federal tax policy and revenue analysis. Weifeng Zhong also gave a brief on the developments in the PCI project since it was presented at the last meetup.

If you missed the meetup, a full video can be found below.

WHAT'S NEXT

Later this month, Zhong will present the PCI project in front of the US-China Business Council, where he will discuss the direction of China’s economic policies and their implications to the trade conflict with the US.

We are also excited to announce more indexes joining the PCI lineup. Beside PCI-Cuba, Julian TszKin Chan, Erin Melly, and Zhong have started analyzing preliminary data for the PCI for East Germany. The PCI for North Korea is another exciting possibility, for which Chan, Zhong, and their collaborators are exploring techniques to digitize its official newspaper, Rodong Sinmun.

WHAT WE'RE READING

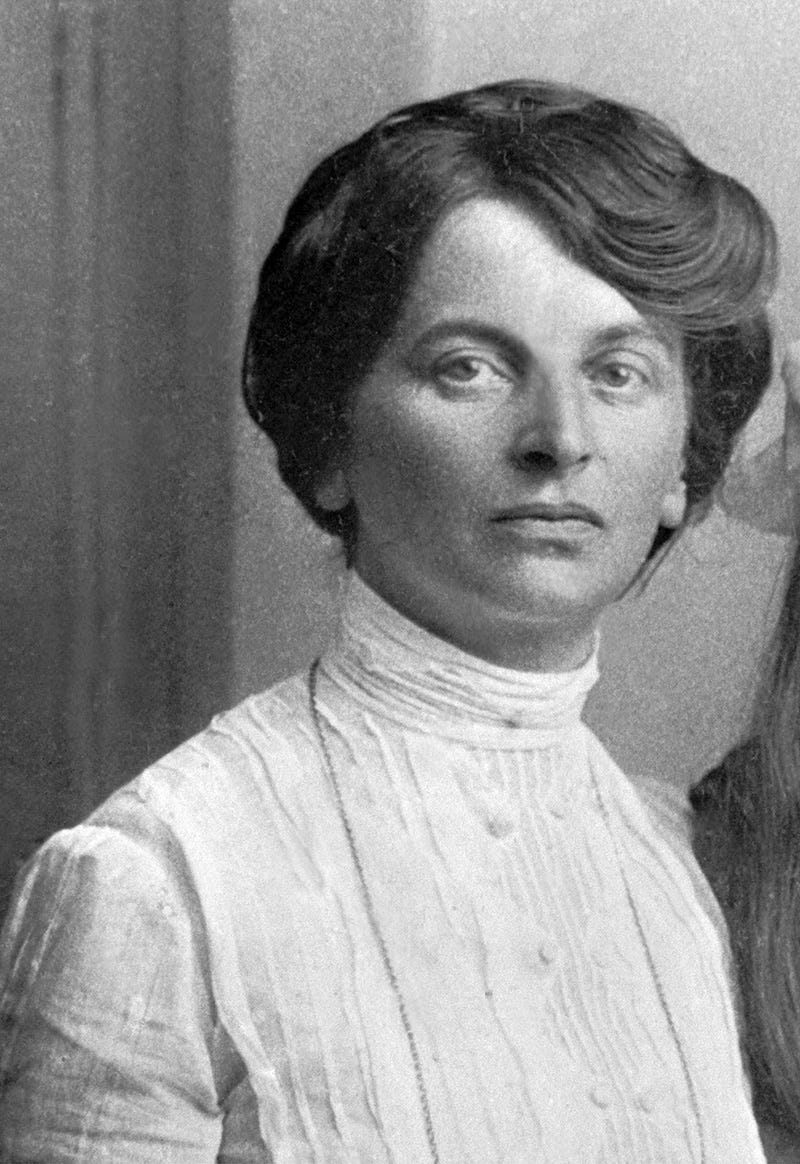

Michael Pearson's “Lenin’s Mistress: The Life of Inessa Armand” (Random House, 2001) is a fun read of the revolutionary’s valentine — no, she’s not his wife. To Armand, Lenin was an idol with much to admire and love. And he certainly reciprocated the feelings, to say the least. “Lenin with his little Mongol eyes gazes all the time at this little ‘Française,’” said the socialist Charles Rappoport.

The two lovers fought for the Bolshevik agenda together — and they fought over it, too. At one point, Armand, a pioneering feminist of her time, was writing about women’s demand for “free love.” Lenin, however, advised her to drop it because it was a “bourgeois, not a proletarian demand.” On and on went a polemic debate between the two darlings, which ended with Lenin’s condescending suggestion: “Have you not some French socialist friends? Translate my points... together with your remarks [to her] and watch her, listen to her as attentively as possible,” so that Armand could realize how foolish Lenin thought her argument was.

We do not endorse this approach to Valentine’s Day.

Inessa Armand in 1909, around the time

she first met Lenin. / Photo: TASS

Edited by Weifeng Zhong and Julian TszKin Chan